(June 2006, MIT Press)

Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal

Abstract

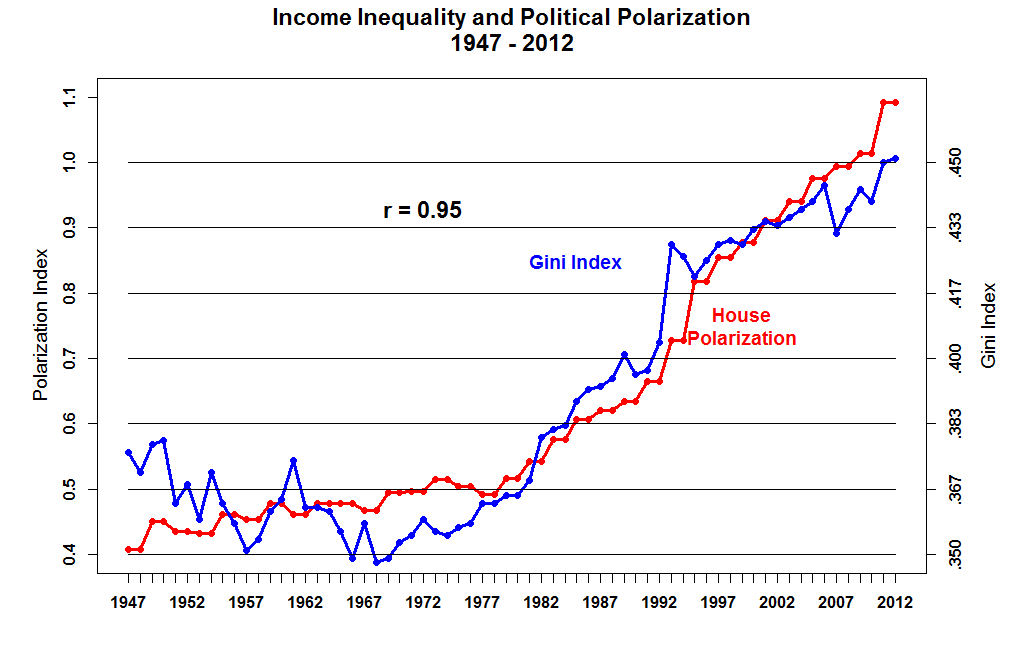

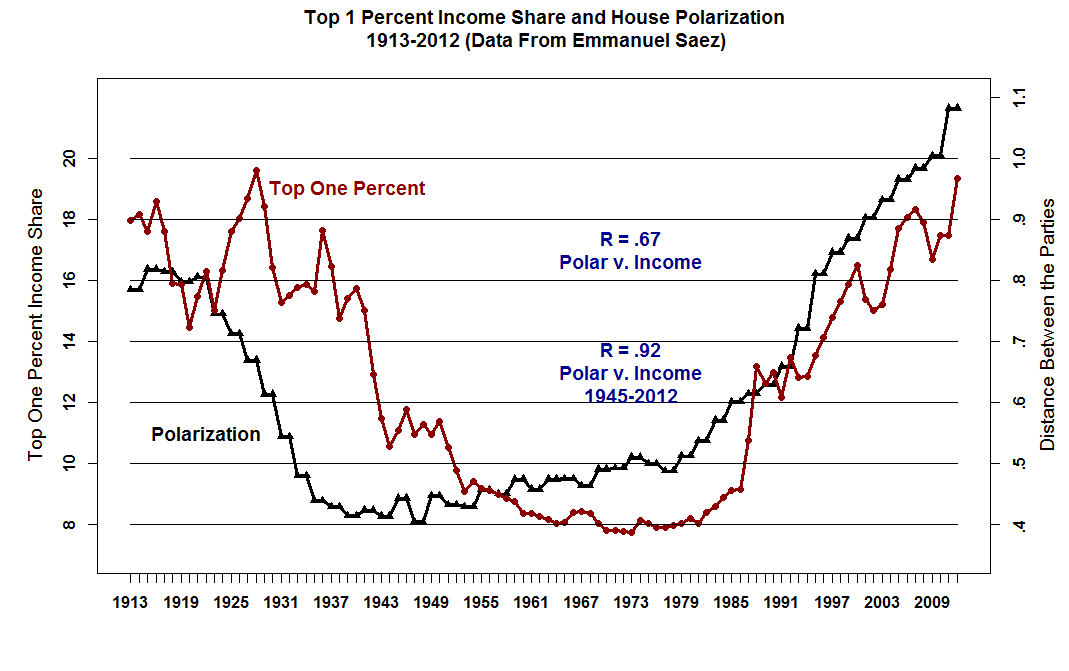

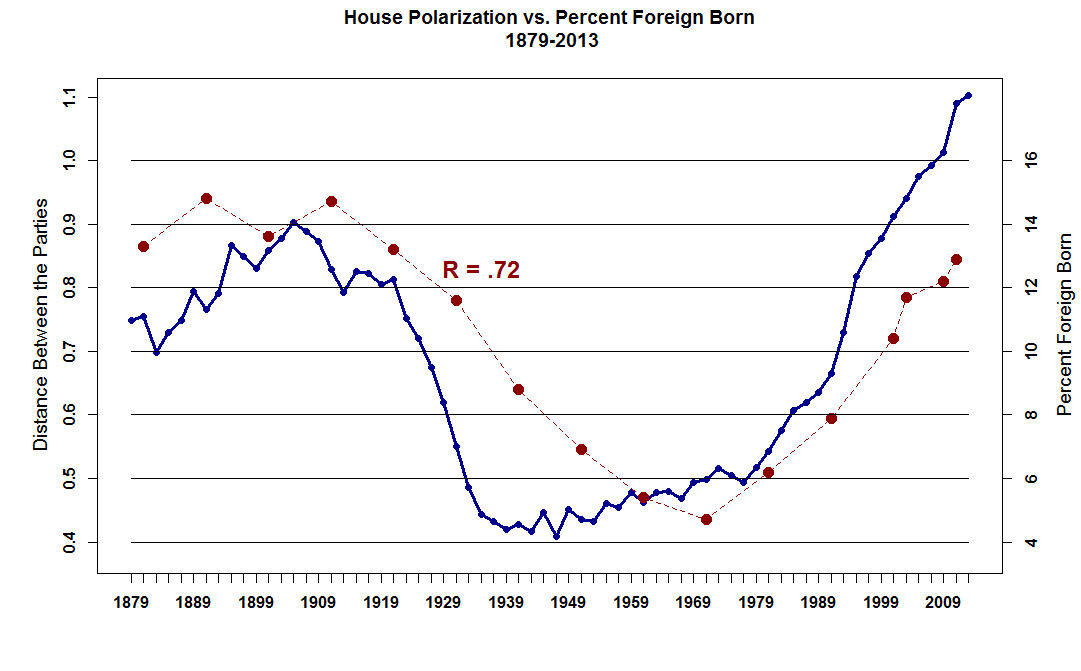

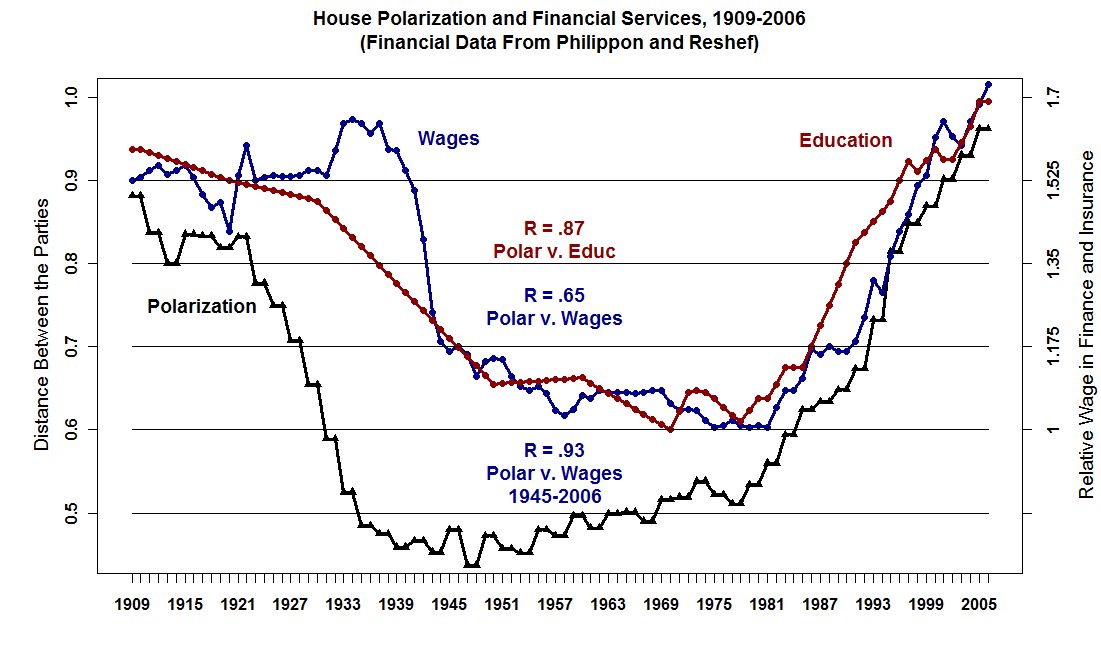

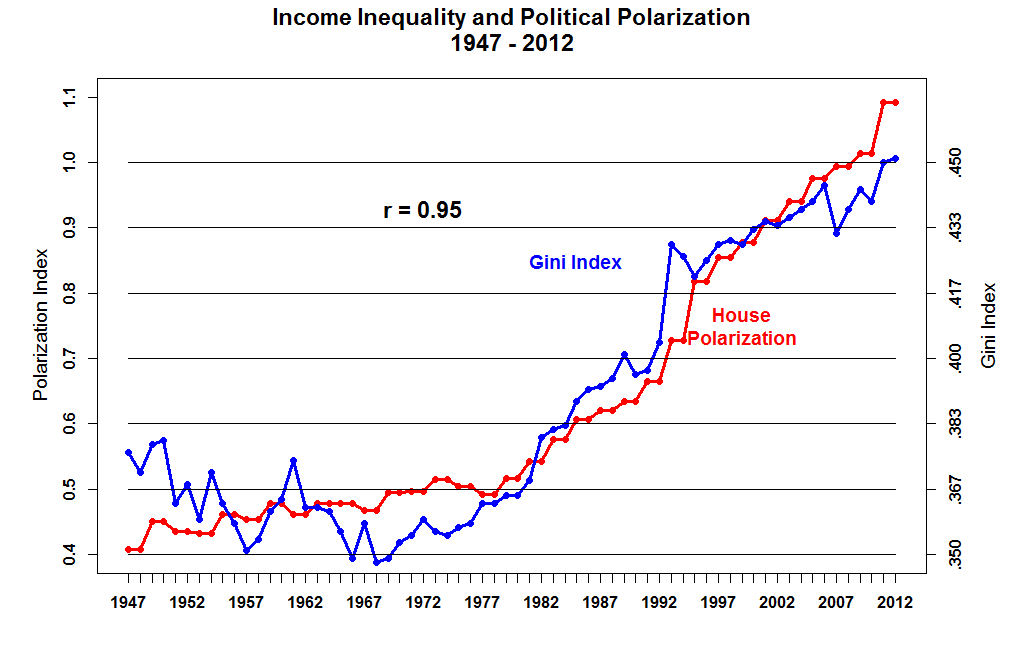

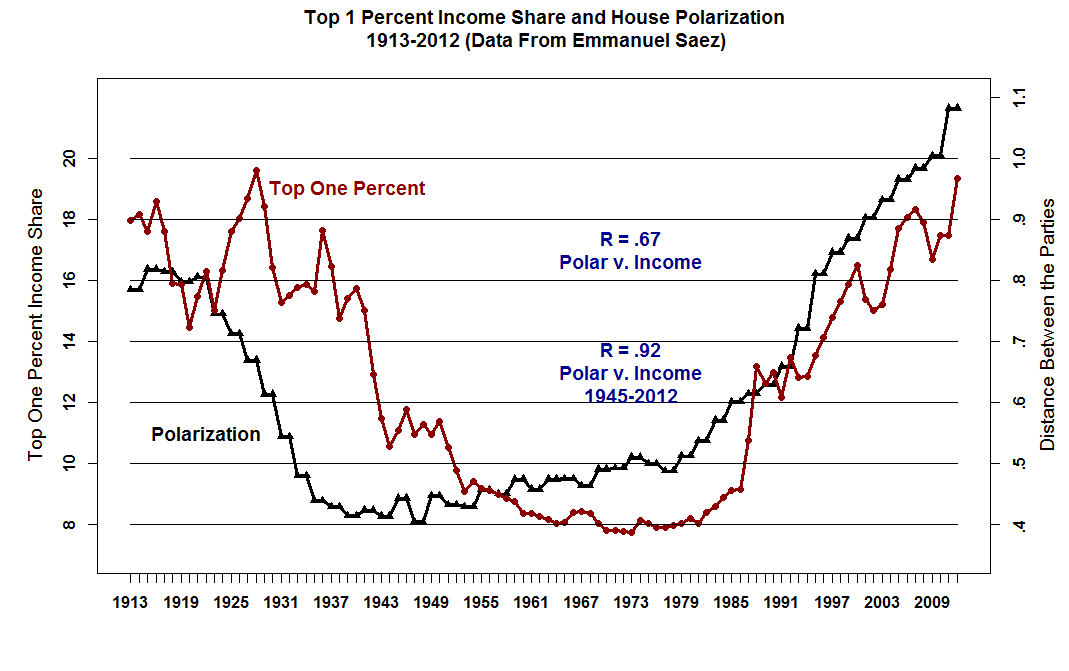

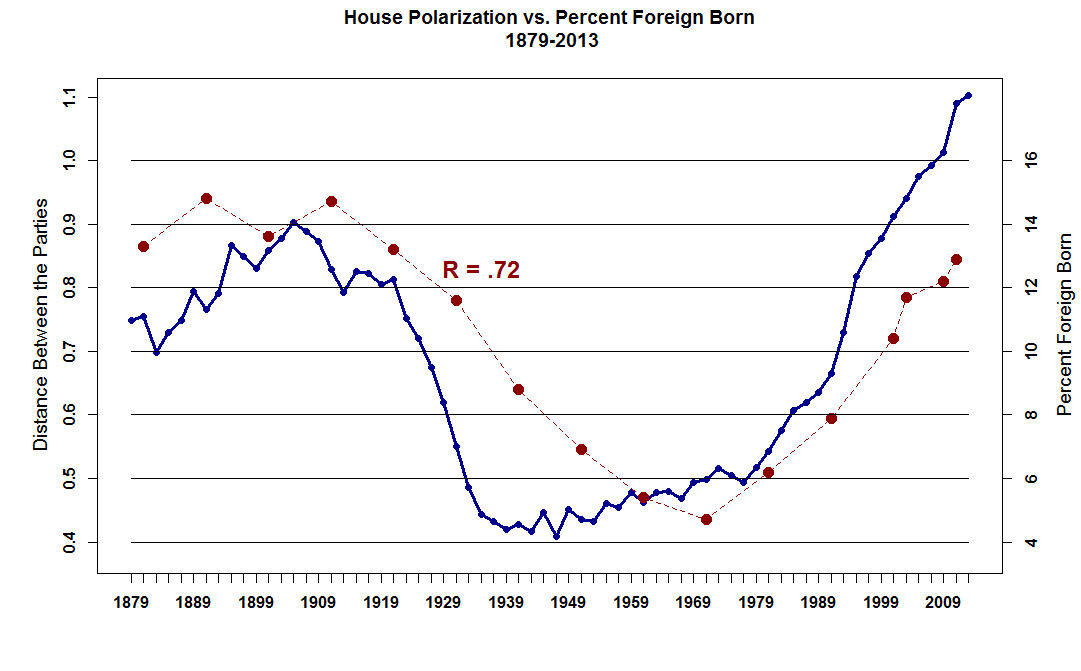

Political polarization, income inequality, and immigration have all

increased dramatically in the United States over the past three

decades. The increases have followed an equally dramatic decline in

these three social indicators over the first seven decades of the

twentieth century. The pattern in the social indicators has been

matched by a pattern in public policies with regard to taxation of

high incomes and estates and with regard to minimum wage policy. We

seek to identify the forces that have led to this observation of a

social turn about in American society, with a primary focus on

political polarization.

Our primary evidence of political polarization comes from analysis of

the voting patterns of members of the U.S. House of Representatives

and Senate. Based on estimates of legislator ideal points (Poole and

Rosenthal 1997 and McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 1997), we find that

the average positions of Democratic and Republican legislators have

diverged markedly since the mid-1970s. This increased polarization

took place following a fifty-year blurring of partisan divisions.

This turning point occurs almost exactly the same time that income

inequality begins to grow after a long decline and the full effects of

immigration policy liberalization are beginning to be felt.

Some direct causes of polarization can be ruled out rather quickly.

The consequences of “one person, one vote” decisions and redistricting

can be ruled out since the Senate, as well as the House of

Representatives, has polarized. The shift to a Republican South can

be ruled out since the North has also polarized. Primary elections

can be ruled out since polarization actually decreased once primaries

became widespread.

It is more difficult to find the causes of polarization than to reject

them because social, economic, and political phenomena are mutually

causal. For example, immigration might lead to policies that increase

economic inequality if immigrants are at the bottom of the income

distribution and do not have the right to vote. We document an upward

shift in the income distribution of voting citizens. In turn,

dispersal in income might lead to polarization. It also might lead to

laxity toward immigration if inexpensive immigrant labor in the form

of domestic and service workers is a complement to the human capital

of the wealthy.

In additional to our focus on the polarization of elected

office-holders, we look at patterns of polarization among economic

elites. By examining campaign contributions, we find very high levels

of polarized giving. While some billionaires clearly spread their

contributions to both parties to buy access, increasing numbers

concentrate their largess on the ideological extremes. This polarized

campaign giving, coupled with the emergence of the soft money loophole

has arguably contributed to the ideological extremism of political

parties and elected officials.

Finally, we also examine polarization among the electorate. While it

is fairly clear that the views of most citizens have not become more

extreme, those with strong partisan identifications have (DiMaggio, et

al., Fiorina). Consistent with other findings (King, Jacobson), we

find that partisans are more likely to apply ideological labels to

themselves and a declining number of them call themselves moderate.

Strong party identifiers are the most likely to define politics and

ideological terms while the differences in the ideological

self-placements of Republicans and Democrats have grown dramatically

since the 1980s. Given Bartels’ findings that partisanship has become

a better predict of vote choice, this polarization of partisans has

contributed to much more ideological voting behavior.

We also find that the polarization of the electorate has increasingly

taken place along economic or class lines. Unlike the patterns of the

1950s and 1960s, upper income citizens are more likely to identify

with and vote for Republicans than are lower income voters. However,

we find that class polarization is most likely a result of the

ideological shift of the Republican Party towards a more economic

libertarian position. This shift to the right was aided by a number

of social, political, and economic factors. First, as American

society has become wealthier on average, a larger segment of society

prefers to self-insure rather than depend on government social

programs. Such voters have become more attracted to the Republicans

and their agenda for an “Ownership Society.” Second, due to patterns

of immigration and incarceration, members of lower income groups are

less likely to be part of the electorate. This has the effect of

moving the median income voter closer to the mean income citizen,

reducing the demand for redistribution (Romer, Meltzer and Richard).

Third, middle-income voters in the so-called “Red states” increasingly

sympathize with Republican positions on social, cultural, and

religious issues (e.g. Franks). The Republican advantage on these

issues has mitigated any loss of votes that might have been associated

with their shift on economic issues. Finally, the emergence of a

class-based, two-party system in the United States has benefited the

Republicans and mirrored the patterns of economic polarization found

in other regions.

Finally, we examine the policy consequences of the fall and rise of

political polarization. The separation of powers makes it difficult

to generate coalitions large enough to produce policy change even when

opinion shifts. We exploit this observation to get some leverage in

disentangling the effects of political, economic, and social policies.

For much of the period when polarization fell, immigration policy was

restrictive and unchanged while income and estate taxes, defined in

nominal terms, became more onerous. For the period since the onset of

renewed polarization, we find strong evidence that “gridlock” has

resulted in a less activist federal government. The passage of new

laws has been curtailed due to the increasing difficulty of generating

the requisite bipartisan coalitions. The effects on social and tax

policy have been especially dramatic as real minimum wages have

fallen, welfare devolved to the states, and tax rates have diminished.

We also show how polarized politics has affected administrative and

judicial politics.

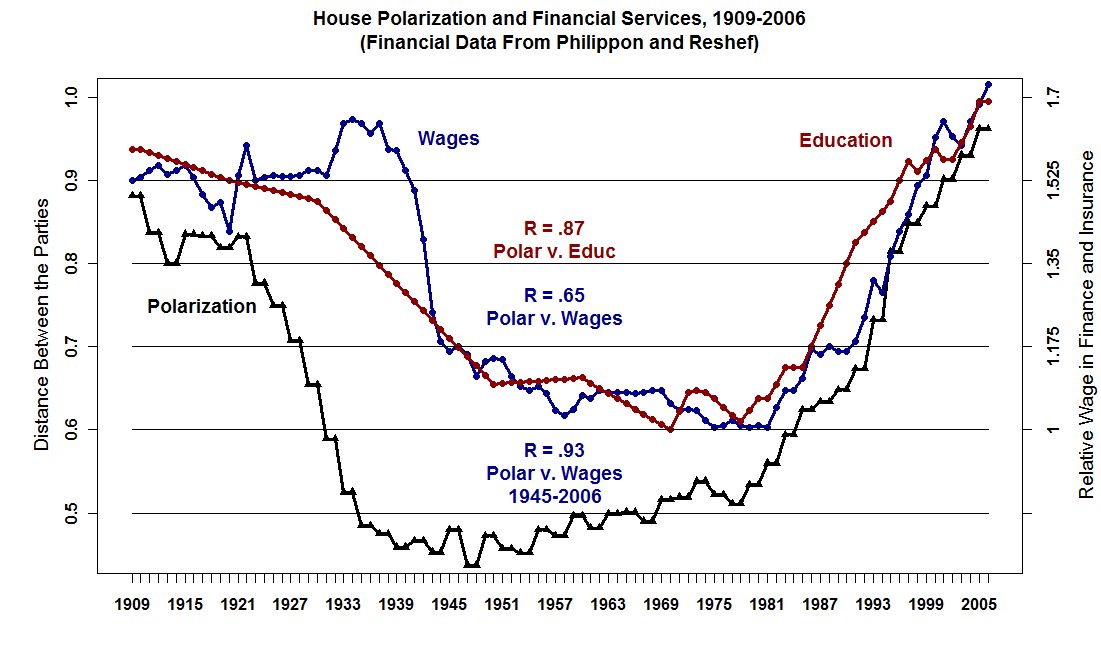

(Of related interest! Note the Patterns. Added, July 2011)

Party Polarization: 1879 - 2015